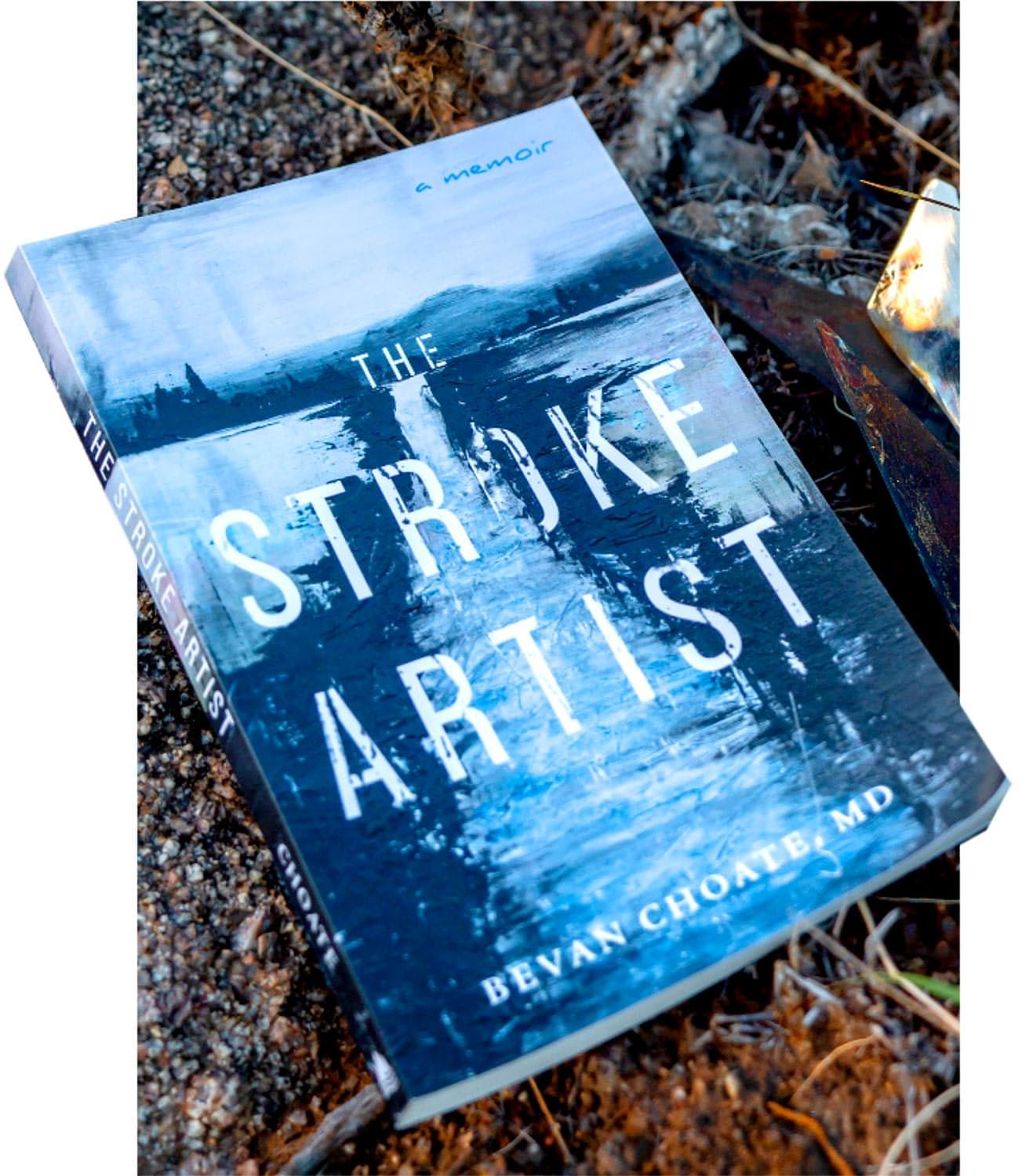

‘The Stroke Artist’

A Tale of Survival, Painting and Urology

ometimes we may “accuse” medical teams of forgetting their patients are human and not just a wristband and chart in a hospital bed; it works the other way, too. We sometimes forget that our doctors are more than white coats adjusting medications and asking, yet again — “Who is the president?” But doctors are, in fact, human. And they can create art. And they can have strokes.

Bevan Choate, MD, was a surgeon and urologist just entering his career. One morning, everything changed.

In “The Stroke Artist,” Bevan Choate, MD, describes “feeling alone and adrift, a victim of a massive stroke.”

Who is Bevan Choate, MD?

“I (was) cowboying since I could ride a horse,” Choate said. “But perhaps due to Waylon and Willie’s song (“Mamma’s, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys”), they didn’t want me to grow up that way. So, I was given all the odd and less glamourous jobs.”

It wasn’t until midway through his undergraduate studies, that Choate began to seriously consider a path in medicine. “I was always a science geek at heart and figured medicine to be a pure and noble application of science,” he said.

Choate excelled in medical school and a five-year urology residency in Albuquerque at the University of New Mexico Hospital. “It was the roughest five years of my entire life,” Choate said. “Being a sleepless subordinate for almost 2,000 days is a tough pill to swallow. Nonetheless, I persevered and began practicing urology in Albuquerque. I did quite a bit of oncology surgery and got good at robotic surgery using the Da Vinci robot. “

At 36 years of age, I was a titan. I was a full-fledged urologist. A urologist is a surgical cyborg and the only surgical specialist mentioned in the Hippocratic Oath (“. . . I will not cut for stone.”) We use lasers to treat stones, robots to yank cancerous prostates, and general irreverence when the going gets tough.

Despite this self-adulatory salvo, I wasn’t much like the surgeons you see on television. I drove a beat-up car, paid down student loans, and genuinely loved my patients. It was my calling, my purpose in life.

I was a titan; not a god. We’ve all at one point or another been privy to the fool with a god complex. Icarus taught us how that story ends. According to some in the medical community, “The only difference between God and a surgeon is that God knows he’s not a surgeon.” Be that as it may, I was not going to be some highfalutin surgeon type. I prided myself in my work in the trenches and strived to improve the lives of my patients.

Things changed for Choate on December 3, 2020.

A left vertebral artery dissection threw a clot that lodged in the left part of Choate’s cerebellum and proceeded to kill millions of valuable brain cells. The dissection has no “attributable etiology.” That’s how doctors write a shoulder shrug emoji. No one knows why it happened. Choate just got lucky.

I had suffered a life-threatening stroke. After nearly dying twice, I ultimately underwent three brain surgeries.

His procedures included a ventricular shunt, a craniectomy, and a left cerebellar strokectomy (surgical excision of infarcted brain tissue post-stroke with preservation of skull integrity, distinguishing it from decompressive hemicraniectomy).

Following this adventure, Bevan contended with a range of acute and chronic deficits — including vision impairment, vertigo, stroke neuropathy, and loss of coordination and fine motor function.

Since then, Choate has accomplished some impressive things, not the least of which are living and walking. He has also returned to his practice and caring for his patients — the laser may need to wait a little while, though.

And, he became a published author and a professional artist.

It’s been quite a memorable two years.

People approach their stroke recovery in different ways. Recovery is a delicate balance of accepting a disability and fighting that disability. Too far in one direction is not great for living the best life possible for many folks.

Choate started writing his book to collect anecdotes. It’s so easy to forget the details of an event with time, especially if we don’t realize at the moment how important they might be.

The very act of writing or typing them out gives them a stronger hold in our memory. Every time we read them again, we can reinforce that hold they have. We can extract more incite from them.

After suffering such a catastrophe, I had no desire to write a book. My friend and former colleague tried to convince me to start writing down the humorous and frankly absurd experiences I endured as a doctor turned stroke survivor. I needed a reason.

He muttered something about posterity and I refused, stating “I don’t want to remember this shitshow.” Yet, I ultimately agreed citing that the act of typing will be an excellent form of therapy for my feral left hand. After a few paragraphs, the storytelling began to take on its own life. I was no longer a titan, and I was now chained to a boulder. Yet, I still had an opportunity to help others by sharing my experiences.

For Choate, writing led to “The Stroke Artist,” … a no-frills divulgence of the microcosm surrounding brain injury, penned from my perspective as a young surgeon.

Bevan Choate, MD, (Medicine ‘13) perfected palette knife painting during recovery from his stroke.

Another outlet for creative expression

Palette knife painting became a hobby for Choate the summer before his stroke. He had enjoyed painting as a child, and picked up this new genre via YouTube lessons, painting just to create art, which is probably the best reason to do it.

Choate returned to art after his stroke to fill his time outside of rehabilitation therapy, and before long he was selling his work online.

“All of a sudden it was like [painting] was something that I had to do instead of something that I just could do,” Choate said. “In some way, the creative process just got better, and I can’t really put my finger on why.”

The relationship between stroke and art is fascinating. It gets into the physical changes in the brain brought on by a stroke, the lifestyle changes we are forced to make, and the shift in our own priorities and world view after a stroke.

Post-Stroke reflections

This doesn’t change the fact that I am now a “mortal” bound to a catastrophic brain injury. From this I learned that no matter how high we think we are flying, humility is right around the corner.

Is it not a god complex to think you can make yourself whole by treating the many parts of others?

Didn’t Dr. Frankenstein try that? Can’t be, right?

I was a titan. I mean, come on, I thought I was the most self-aware doctor on the planet.

I realize now that my true life had been on life-support prior to my stroke. I previously avoided community and fellowship because my poorly evolved brain thought I was getting it in spades daily in a hospital.

My relationships with friends and family suffered throughout my years in medicine. I somehow managed to avoid those that gave me a chance to be vulnerable, self-reflect and be fulfilled.

I was always too tired or too busy. To a brain, simulation is the same as reality. To a heart, it’s a dreadful cancer.

Now, more than ever, we need to come together in a way that our hearts can enjoy. It only took a stroke and writing a book for me.