Feature

FeatureFrom Submarines to Childhood Cancer Research

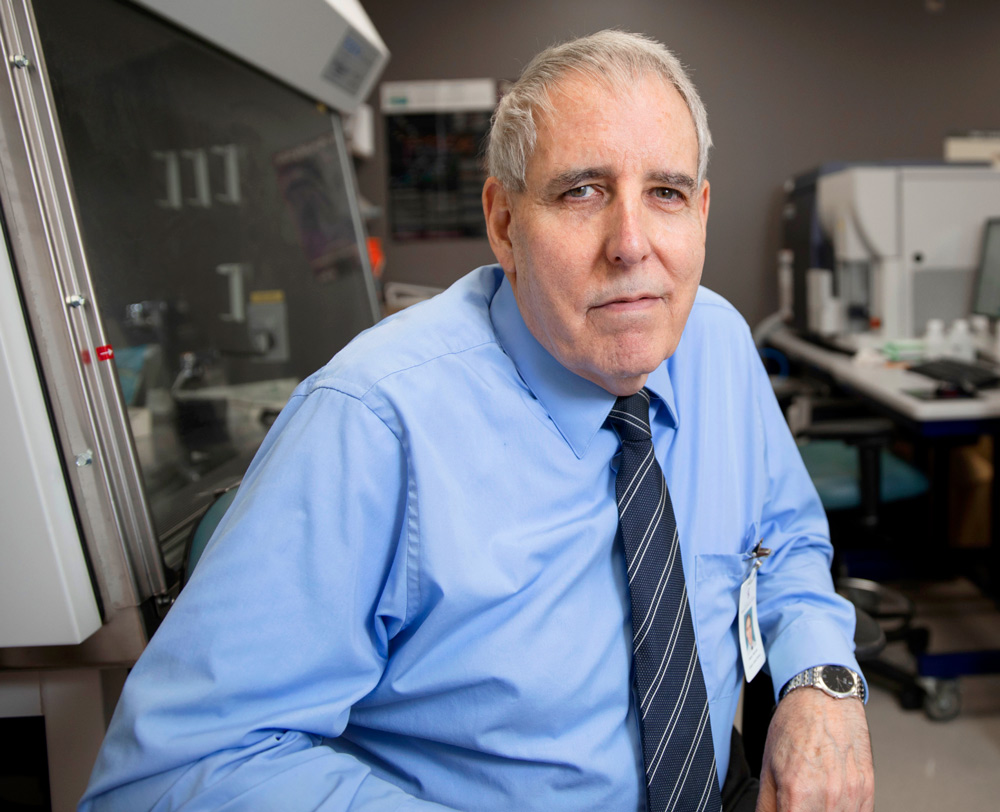

s a young member of the Navy ROTC growing up in El Paso, Texas, and then attending the University of Texas at Austin (UT), C. Patrick Reynolds, MD, PhD, had a specific career goal: to serve as a nuclear weapons officer aboard a nuclear submarine. In addition to weapons, Reynolds also was interested in biology and biological research, so that became his major.

During spring break of his sophomore year, Reynolds and his Navy ROTC roommate spent a week aboard the USS Patrick Henry, a nuclear submarine docked in Charleston, South Carolina. The medical officer aboard discovered Reynolds was a biology major and encouraged him to switch to pre-med.

Reynolds reminded him Navy ROTC regulations said pre-med majors were not allowed. The medical officer showed Reynolds new instructions, which opened up its program to pre-med majors. However, Reynolds interest remained low.

Once aboard the nuclear submarine, Reynolds and his roommate found themselves in the middle of what was known as Sherwood Forest, an area with 12 ballistic missile launch tubes loaded with 300-kiloton nuclear warheads.

“We were silent; we were speechless,” Reynolds says. “We saw somebody labeled the top of the fire control (launch) sequence buttons with ‘To Russia with love,’ and at the bottom they put ‘Repent.’ It got to me, and I started thinking about what I was training to do, and what this sub was capable of doing.”

Reynolds returned to Austin, changed his major to pre-med and went to the Navy ROTC office to tell them what he was doing. The office told him doing so would lead to his removal, but Reynolds showed them the new instruction.

The things he learned in that early class at UT, where he studied bacteria and how bacterial spore formation affected gene expression spurred an interest in cancer research.

At UT, Reynolds read a paper written by C. Everett Koop, MD, DSc, the U.S. surgeon general from 1982 to 1989, and Audrey Evans, MD, a British physician considered to be the Mother of Neuroblastoma.

“In the article, they had described (neuroblastoma) patients that would spontaneously regress; their cancer would just go away on its own,” Reynolds says. “And I thought that if it’ll go away on its own, we can make it do it; we can figure out how to make it regress.”

After a years of fortuitous events, chance meetings and generally being in front of the right people at the right time, Reynolds took his joint MD/PhD degree from UT and eventually made his way to UCLA and then to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“At (Children’s), we ran a Phase I clinical trial of Accutane®, a retinoid we had shown could turn off the major oncogene driving neuroblastoma and stop the tumor cells from growing,” Reynolds explained. “Finally, the idea I had back when I was a sophomore in college turned out to be true: We got multiple complete responses in the bone marrow of these kids with neuroblastoma, and we managed to take that into a Phase III clinical trial that resulted in Accutane® being part of standard-of-care treatment for neuroblastoma worldwide. That’s when I decided what I really wanted to focus on was drug development.”

Despite his success, Reynolds and several lab team members at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles were unhappy in California. He heard about a physician-researcher in Lubbock, Harry Weitlauf, MD, who had convinced Steven Berk, MD, TTUHSC’s medical school dean, to recruit a cancer investigator who could help the university establish a cancer center. A deal was agreed upon, and Reynolds, along with Barry Maurer, MD, and Min Kang, PharmD, moved their labs to TTUHSC.

“The Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) has been incredibly good about funding childhood cancer research and making opportunities specifically available to childhood cancer investigators,” Reynolds says. “That’s the other thing about Texas: it cares about kids, which I can’t say for every place.”

—By Mark Hendricks

Global Childhood Cancer Research Finds a Hub at TTUHSC

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Childhood Cancer Repository, located at TTUHSC Lubbock, plays a role in many of these research projects.

The Childhood Cancer Repository provides validated patient-derived cell lines and cryopreserved patient-derived xenografts (PDXs; human tumors growing in special mice) established from childhood cancers to all investigators who request them.

“The (COG) sends us living cancer cells from patients, and we grow the cell lines and PDXs here at TTUHSC,” C. Patrick Reynolds, MD, PhD, director of the School of Medicine Cancer Center, says. “We characterize them and make them available. So far, we’ve sent them to 30 countries, and more than 500 labs use them.”

Reynolds also directs the Childhood Cancer Repository, a resource laboratory for the oncology group, the national cooperative for childhood cancer research in the U.S. and the world’s largest organization devoted exclusively to childhood and adolescent cancer research.

Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation — started with a lemonade stand run by Alex, a child who died from neuroblastoma — funds the repository, known today as the Children’s Oncology Group – Alex’s Lemonade Stand Repository. Core funding for TTUHSC’s animal facility that supports the repository is provided by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT). Characterization of cell lines and PDXs in the repository is supported by CPRIT, the National Cancer Institute and the Department of Defense.

Excerpts from the CURRICULUM VITAE of

C. Patrick Reynolds, MD, PhD

EDUCATION:

PRESENT POSITIONS:

Publications (as of November 2024):

- 257 research articles in peer-reviewed journals

- 70 invited articles and review chapters