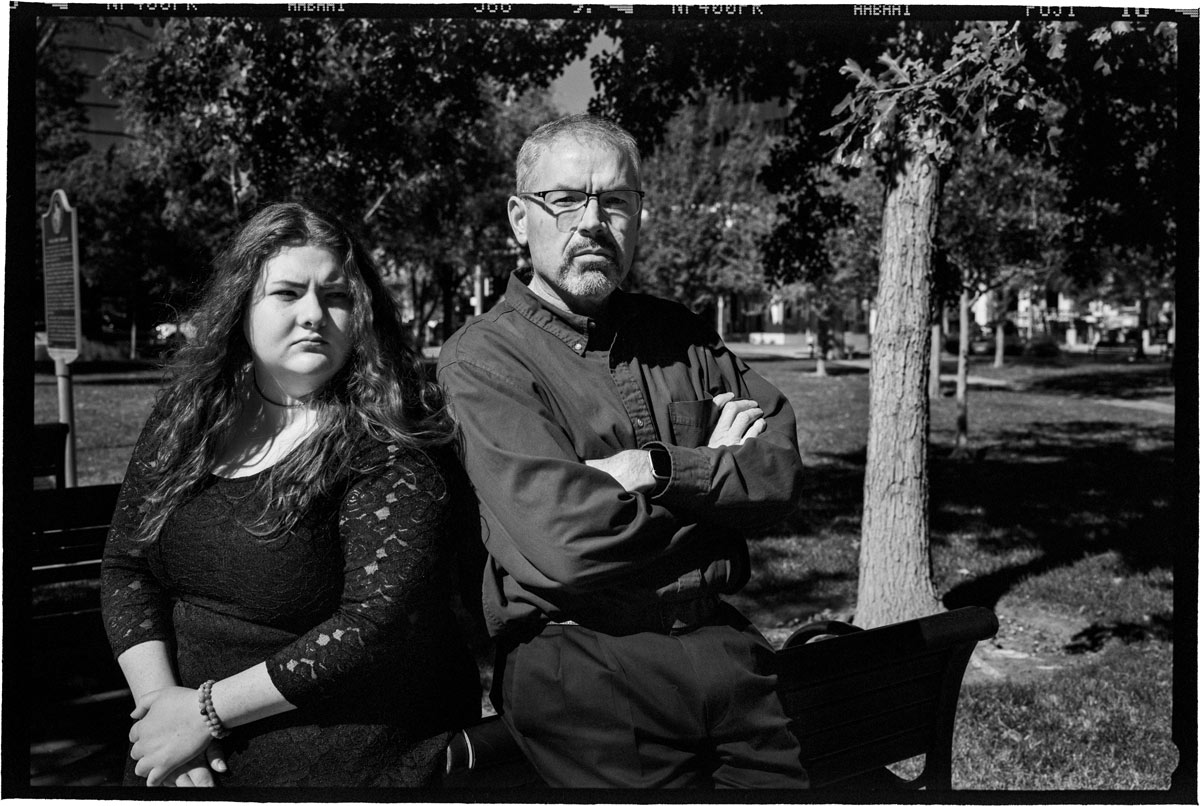

Nursing Supervisor, TTUHSC Larry Combest Community Health and Wellness Center

Nursing Supervisor, TTUHSC Larry Combest Community Health and Wellness Center

The Humans Behind the Heroes

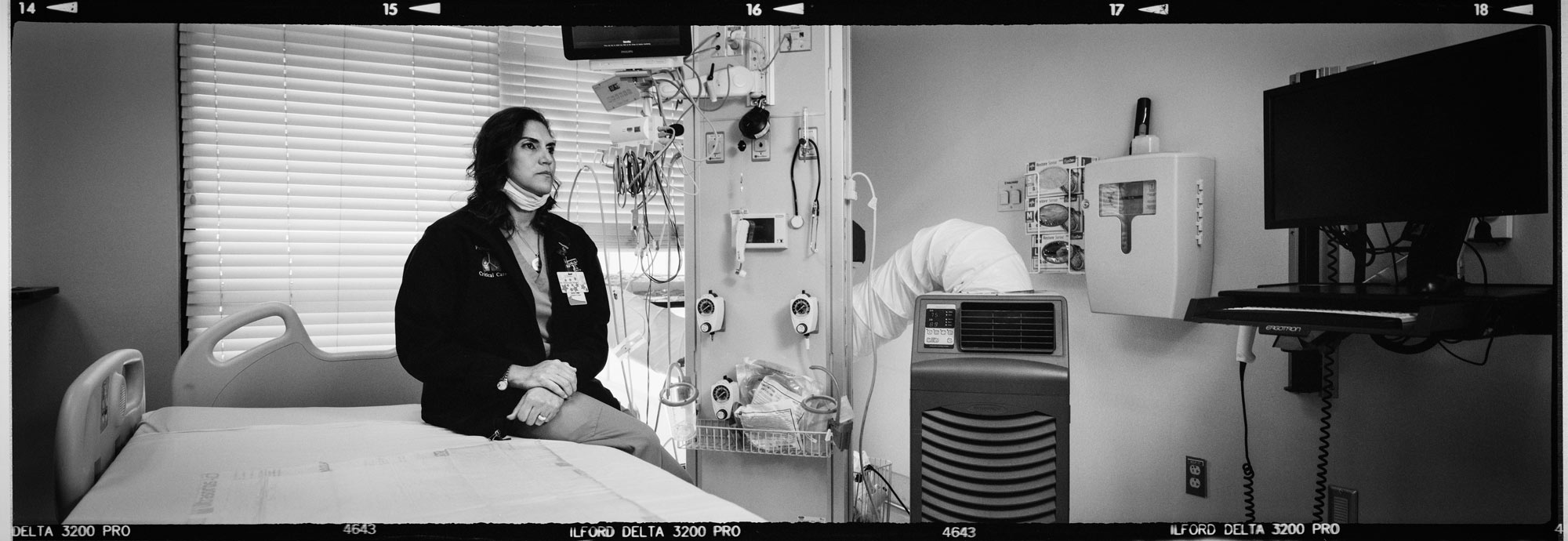

overed in layers upon layers of personal protective equipment, Ebtesam Islam, MD, PhD, FCCP, (Resident ’16, ’13; Medicine ’09; Biomedical Sciences ‘05) spends five hours stabilizing one patient. Sweat drips down her back as she does chest compressions, shouting orders so she can be heard through her mask. Up to six people in the room giving medications, stabilizing the airway, starting intravenous fluids, etc. — it’s stressful, but she remains steadfast in the work. “It’s somebody’s life,” she adds. “And you want so bad to save them.”

As a pulmonary and critical care physician in the medical intensive care unit at University Medical Center in Lubbock, Texas, Islam treats the sickest of the sick. But previous patients have not compared to the challenge of caring for a COVID-19 patient. Every hour of every 12-hour shift, she’s pushed to the very limits of her abilities and stamina.

And it’s taking a toll. “The nurses and I talk about burnout,” Islam acknowledges. “We’ve all gone home and cried. We’ve all cried at work.”

Now, even with an increase in vaccine availability, COVID-19 surges with no clear light at the end of the tunnel. “We’re human,” Islam says, pausing to collect herself. “We take on a little piece of every patient who passes away.”

Mental Health America’s 2020 survey, “The Mental Health of Health Care Workers in COVID-19,” shows more than three quarters of health care workers nationwide reporting exhaustion and burnout — Islam and her colleagues are far from alone.

The need to prioritize mental health care for health care providers was significant long before COVID-19 hit American shores, as burnout was a hot topic among health care professions. However, the pandemic made mental health not only a priority for health care workers, but also a necessity. “The pandemic has shown that we need each other, more than ever,” said Zach Sneed, PhD, assistant professor in the School of Health Professions Department of Clinical Counseling and Mental Health. “People just really need each other.”

You’re Not Alone

“When working with residents and medical students, I’ve found that the struggle is to just be human,” said David Trotter, PhD, associate professor in the School of Medicine and clinical psychologist. “We want to resist that struggle as health care workers, when, really, the struggle is OK. We have resources to treat mental health issues, and it doesn’t make you weak to access them — in fact, if you’re not struggling mentally in the health care industry right now, that’s worrisome.”

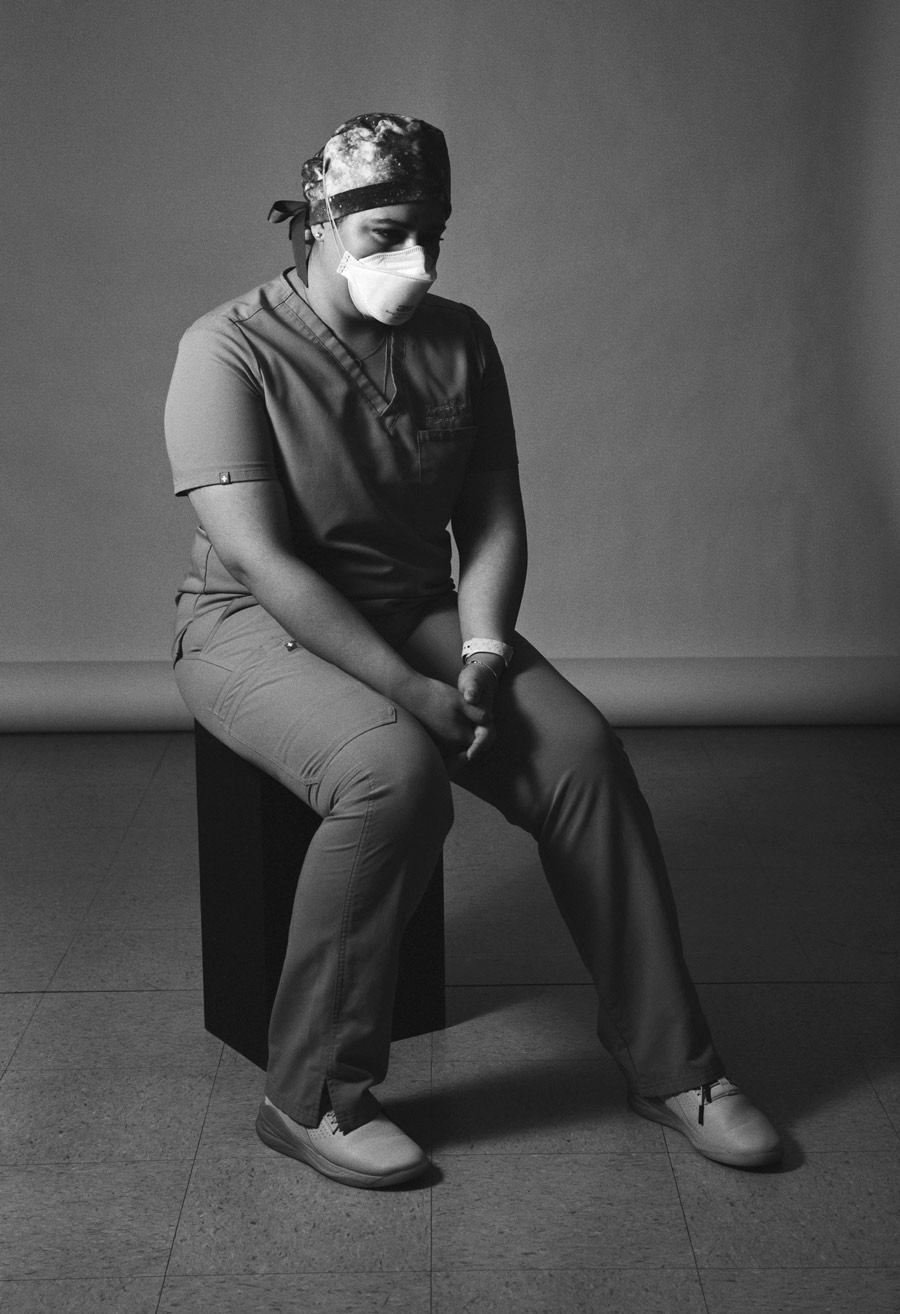

Brittany Simpkins, MSN, RN, (Nursing ’15) a nursing supervisor at the Larry Combest Health and Wellness Center, grasps for words to describe the feeling that settles in after the long days. Angry. Upset. Exhausted. None feel adequate. “It’s like getting mad at an iron bar,” she says of her simmering frustration. “If you kick it, you only hurt yourself.”

Before COVID-19, mental health concerns for health care professionals were a significant problem — but it was also something that many felt reluctant to share.

No more. “There has been a sense of universality,” says Logan Winkelman, PhD, LPC, assistant professor in the School of Health Professions Department of Clinical Counseling and Mental Health. “Before, it might have felt like there were just a handful of individuals feeling exhausted or experiencing anxiety and depression. But when the pandemic hit, nearly everyone felt that way. People felt better just knowing they weren’t alone.”

Is There a Solution?

pulmonary and critical care physician University Medical Center

While the path to a solution is murky, one thing is clear: empty platitudes that highlight the importance of self-care aren’t going to cut it for health care workers anymore. “Other physicians have repeatedly told me, ‘I don’t want one more person telling me to ‘take a shower and relax,’ or ‘do 20 minutes of meditation,’” says Sarah Wakefield, MD, associate professor of psychiatry at the School of Medicine. “They want real change on a systemic level.”

Where There is Crisis, There is Opportunity

Within the uncertainty of what needs to happen next for health care workers and their mental health, there is determination to solve the problem — whatever it takes. “This has been a terrible crisis, but there is also an opportunity,” Trotter says of this inflection point in health care. “Let’s not let it go to waste.”

Editor’s Note: Do you have ideas on addressing mental health for the health care industry? Join the conversation.

In Their Own Words

I still have nightmares.

Things started picking up in May (2020), and by July, it was pure chaos. The time I spent in the ICU tripled. Half of my co-fellows got sick with COVID-19. Because I was chief fellow, I was the one organizing schedules and backup teams.

Everyone was scared. There were nights I would stay up until midnight reading European journals. I was scared of getting sick and bringing the virus home to my family. I was often at the hospital for more than 12 hours a day.

But you just buckle down and do the work.

Normally on my ICU rotation, which lasts for a month, I can go three weeks before the fatigue kicks in. COVID-19 was different. I was exhausted after the first week. It was so intense. I would come home, go to sleep, wake up and do it again.

Usually, before COVID-19, I thrived by compartmentalizing my life. But this past year and a half, I had trouble separating things. I would come home and think about the patients. I would check how they were doing on my computer. I had two patient deaths that were very traumatizing — so fast, so out of the blue. I still, to this day, have nightmares about that. Coping with loss had never been this big of an issue for me before.

In the ICU, you see death every day. But this felt so different. The patients were so, so sick. And, they were completely alone. Half the time it was just me, the nurse and a respiratory therapist in the room as they were dying.

One thing that has kept me sane is exchanging stories and talking about it with others in the health care community. I can say to them, ‘I tried to save this patient’s life for an hour and a half, and they still died,’ and they understand what it’s like. If I kept it bottled up inside, I don’t think I would make it.

But, through it all, you can’t lose your compassion for other human beings. Life is precious, no matter what.

The plexiglass divide.

Lee Ann Hampton, PharmD, (Pharmacy ’02) is the owner of Paris Apothecary in Paris, Texas.

I press on in honor of those I’ve lost.

Debra Atkisson, MD, DFAPA, ACC, (Medicine ’86) is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor at TCU and UNTHSC School of Medicine in Fort Worth, Texas.

In the middle of the sea with no lifeboat.

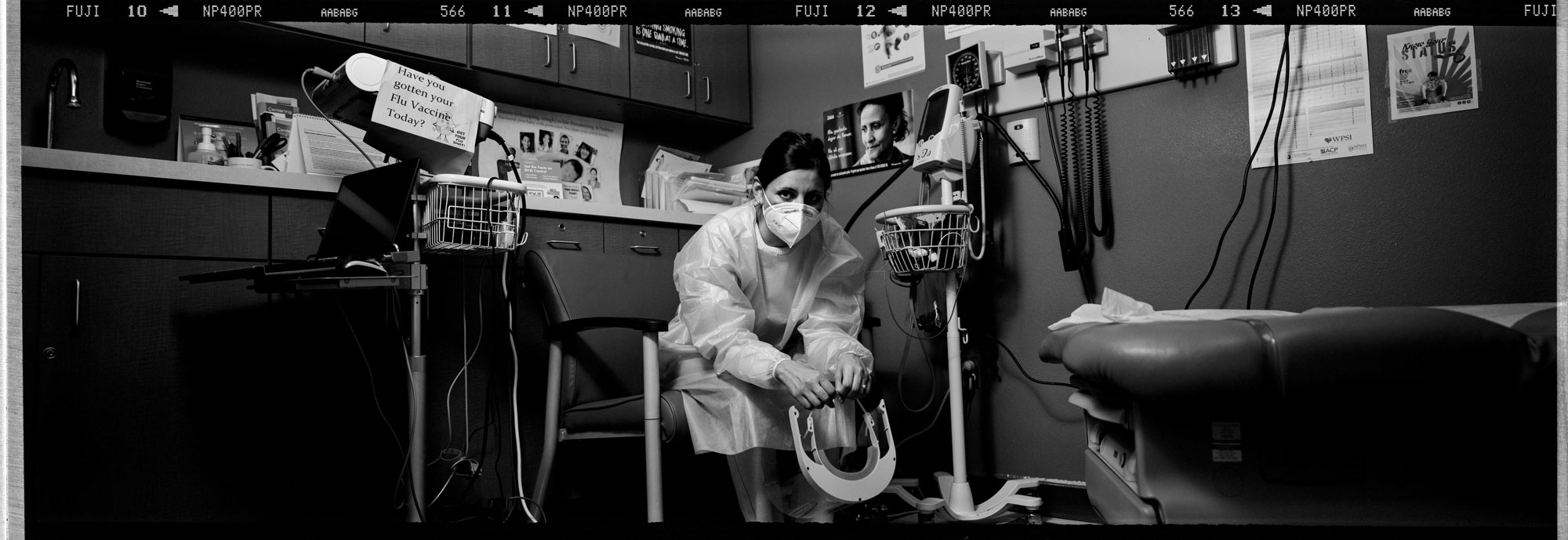

When the world shut down in March 2020, I initially felt so glad that I had gotten out at the right time. But then I felt guilty that I wasn’t helping. I’m a nurse. It’s what I’m made to do.

So, I applied for this job.

A lot of the patients I work with are in survival mode all the time. I can change my mask as much as I need to, but they might find a mask on the ground and use it. People deal with things like COVID-19 differently when they’re worried about finding their next meal.

COVID-19 is like an invisible fire. We’re telling people to stay away from it, but they run into it and then beg us to put it out. We’re pleading with everybody to do basic things.

It hurts your heart when you know you tried everything to give someone the resources and knowledge to stay safe, and somebody sneezes behind them at Walmart, they get COVID-19 and die. That’s somebody’s dad. You saw that person smile behind their mask when you told them a joke. You develop relationships. And then you lose them. It makes me tired.

Sometimes, I feel like I’m in the middle of the sea with no lifeboat. Even though I know that people are grateful and while many patients say thank you, I still sometimes feel like I’m floating alone.

If I can just get through the next patient.

When I came home from work, I changed in the garage, swabbed myself down with hand sanitizer and went straight to the laundry room. I put my scrubs in the laundry, then went inside and took a shower. Only then could I greet my family. I knew some providers who temporarily lived in converted RVs to keep their families safe.

It took hours to do everything, and I felt invisible. A lot of us did.

While other people were complaining about being locked down, working from home and slow internet speeds, we were driving to that gray unit every day, putting on our PPE and taking care of sick inmates who lost what little comforts they had before all of the restrictions.

Some units had no COVID-19 cases for the longest time, and then an employee would come in with it unknowingly, and it was off to the races. It was a taxing, miserable existence to go in there every day. It was exhausting — you’d have that one-thousand–yard stare.

I remember a moment in June at a meeting when my boss said I sounded desperate. She was right. I was overwhelmed.

I couldn’t think about the future. I felt like I was crawling, and I’d just say to myself, ‘I’m just going to see the next patient. If I can get through the next patient, then I’ll see what happens.”

All you can do is say, ‘What can I do right now for this patient?”

Do I think about leaving this job? No. I can’t imagine not doing this. Sure, some of the people I care for say horrible things to me. They can act bonkers. But you still have to take care of them as much as they’ll let you. This is a calling. And no matter how bad it gets, this is what I’m going to do.

I want normal, too.

Resources

Chemical Dependency

Texas Covid Mental Health Support Line

The Counseling Center @ TTUHSC

StarCare Crisis Line

800-687-7581