In All Things of Nature, There is Something of the Marvelous

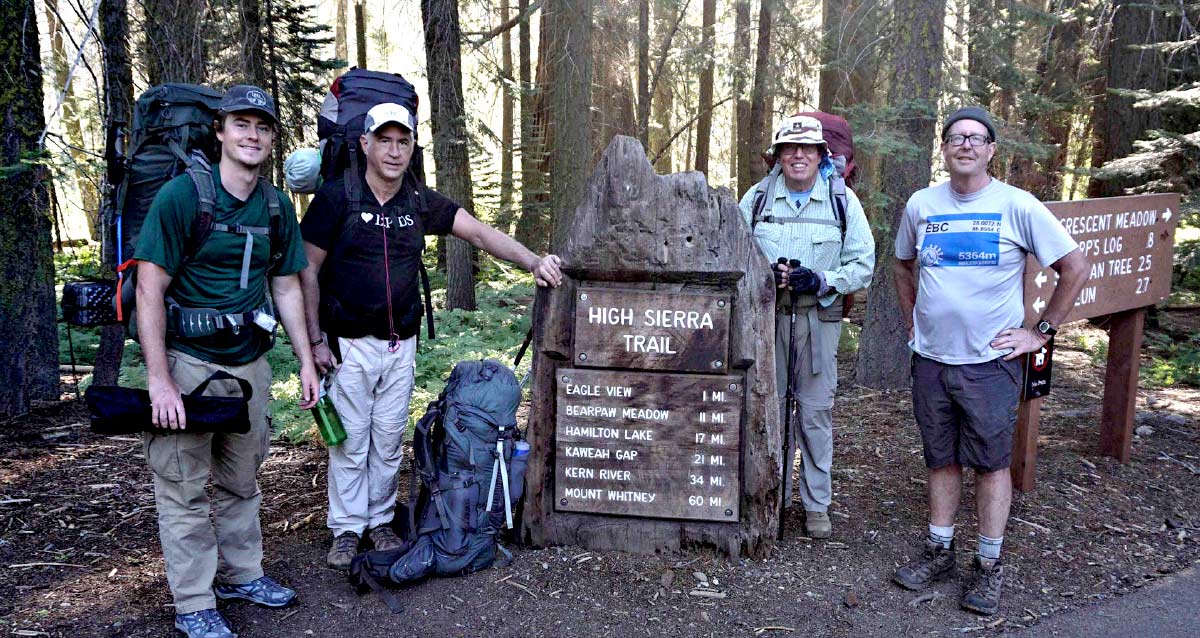

tanding atop California’s Mount Whitney, Thomas Pressley and Michael Blanton gazed in awe at the surrounding peaks of the Sierra Nevada below them. At 14,500 feet, they had reached the highest point in the continental U.S.

The view was breathtaking — literally, Pressley quips. At that altitude, it’s a challenge to breathe.

Blanton reaches into his backpack, pulling out the four cans of Texas Shiner beer he hauled up the mountain to toast their group’s achievement. In that unspoken moment, the duo reflected on just how far they climbed, yet there were greater heights to reach.

It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it …

Of course, the trek to its peak has killed hundreds of people and, as Blanton explains, the club has an unspoken rule: no matter what they go through along the way, “It doesn’t really count until we get back alive.” After researching the possibility of hiking to the famous base camp of Mount Everest, Blanton realized even amateur hikers can make the climb.

Thus began two years of intensive planning, logistics, vaccinations, remedies for altitude sickness, etc. For Blanton, PhD, a University Distinguished Professor, TTUHSC research integrity officer, associate vice president for Research and director of the MD-PhD program, preparation was half the fun.

Well begun is half done …

“We were proud of ourselves just walking up the steps,” Blanton recalls. “Yet, here’s a guy carrying 200 pounds of store supplies.”

They couldn’t yet see Everest, but there were plenty of other sights: The peak of Ama Dablam, aptly named, as it resembles a mother hugging her children. A Yeti foot and skull on display in a monastery, which they paid to see because they couldn’t pass up such an opportunity. At 12,000 feet, they watched a rugby game on TV at an Irish pub at the highest elevation in the world.

They slept in rustic plywood structures called tea houses. On the ground floor was a communal space for cooking over a stove fueled by yak dung, eating and soaking up whatever warmth they could. At nightfall, the climbers retired to cots upstairs, relying on their sleeping bags to retain body heat. With no running water, the toilet situation was primitive. At best, there may be a normal looking toilet that required manual flushing — refilling the tank one scoop of water at a time — while at other times there was just a hole in the ground.

And yet, the tea houses all offered Wi-Fi. One had espresso and a German bakery, so Blanton, Pressley and Sutton ate and drank while watching the movie “Everest.”

There is no great genius without some touch of madness …

At 16,000 feet, even basic human functions became difficult. Eating lost its appeal. They had headaches. They couldn’t sleep. When they did sleep, their starvation for air would jar them awake, sucking in mouthfuls, yet not getting nearly enough.

Nightly hyperventilation would test anyone’s limits, but they pressed on. Base camp was at 17,500 feet — they were too close to quit.

As they neared base camp, the friends had expectations of what they would find. They knew there wouldn’t be the sea of tents marking expeditions to the summit; most attempt the ascent only in the spring. It was November. Blanton expected a beautiful open plain like he saw in California. Instead, they found an unremarkable, flat, rock-covered area — the moraine of a glacier.

Everest, which eluded them the entire trip, now peeked over the surrounding mountains, teasing them with just a glimpse of its tip. Even with anticlimactic scenery, they were thrilled to reach their goal.

This time it was Pressley who carried libations for the celebration. He removed the flask of cognac he had saved in his pack for this moment, and they all sipped, savoring their triumph. Sutton pulled a Texas Tech University flag from his pack for the obligatory photos. Then, as their excitement ebbed into quiet satisfaction, they watched as the next group of hikers reached base camp and the cycle of celebration began again.

The whole is more than the sum of its parts …

From 18,500 feet, he looked up, up, up finally spotting the elusive peak another 10,000 feet above.

“Even though you’re so proud of yourself that you’ve gotten this high, it’s so much higher to the top,” he said. “That’s when you truly appreciate how much more human effort it takes to get to the top of Everest.”

Heading back toward Lukla, Blanton caught up to Pressley and Sutton a few hours later.

“How many people get to go to Everest?” Sutton said. “Even to go to the base of it, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience. And it’s certainly an adventure all the way around.”

None of them have any plans — yet — to climb Everest itself. However, they plan on riding the adrenaline high of this adventure to the next one. After all, the adventure is its own reward.